基于Python3 神经网络的实现

发布时间:2019-09-26 07:23:24编辑:auto阅读(2764)

基于Python3 神经网络的实现(下载源码)

本次学习是Denny Britz(作者)的Python2神经网络项目修改为基于Python3实现的神经网络(本篇博文代码完整)。重在理解原理和实现方法,部分翻译不够准确,可查看Python2版的原文。原文英文地址(基于Python2)

概述如何搭建开发环境

安装Python3、安装jupyter notebook以及其他科学栈如numpy

pip install jypyter notebook pip install numpy123123

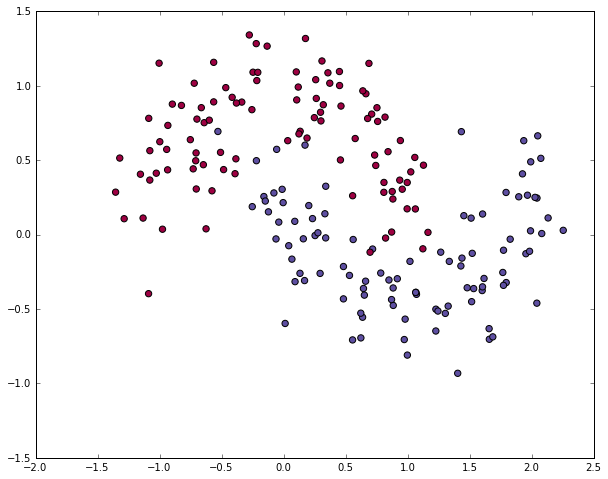

生成测试数据集

# 导入需要的包 import matplotlib.pyplot as plt import numpy as np import sklearn import sklearn.datasets import sklearn.linear_model import matplotlib # Display plots inline and change default figure size %matplotlib inline matplotlib.rcParams['figure.figsize'] = (10.0, 8.0)12345678910111234567891011

生成数据集

make_moons数据集生成器

# 生成数据集并绘制出来 np.random.seed(0) X, y = sklearn.datasets.make_moons(200, noise=0.20) plt.scatter(X[:,0], X[:,1], s=40, c=y, cmap=plt.cm.Spectral)12341234

<matplotlib.collections.PathCollection at 0x1e88bdda780>

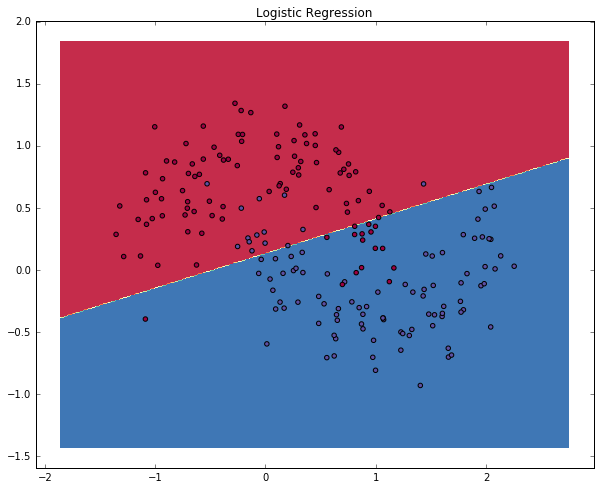

逻辑回归

为了证明(学习特征)这点,让我们来训练一个逻辑回归分类器吧。以x轴,y轴的值为输入,它将输出预测的类(0或1)。为了简单起见,这儿我们将直接使用scikit-learn里面的逻辑回归分类器。

# 训练逻辑回归训练器 clf = sklearn.linear_model.LogisticRegressionCV() clf.fit(X, y)123123

LogisticRegressionCV(Cs=10, class_weight=None, cv=None, dual=False, fit_intercept=True, intercept_scaling=1.0, max_iter=100, multi_class='ovr', n_jobs=1, penalty='l2', random_state=None, refit=True, scoring=None, solver='lbfgs', tol=0.0001, verbose=0)

# Helper function to plot a decision boundary. # If you don't fully understand this function don't worry, it just generates the contour plot below. def plot_decision_boundary(pred_func): # Set min and max values and give it some padding x_min, x_max = X[:, 0].min() - .5, X[:, 0].max() + .5 y_min, y_max = X[:, 1].min() - .5, X[:, 1].max() + .5 h = 0.01 # Generate a grid of points with distance h between them xx, yy = np.meshgrid(np.arange(x_min, x_max, h), np.arange(y_min, y_max, h)) # Predict the function value for the whole gid Z = pred_func(np.c_[xx.ravel(), yy.ravel()]) Z = Z.reshape(xx.shape) # Plot the contour and training examples plt.contourf(xx, yy, Z, cmap=plt.cm.Spectral) plt.scatter(X[:, 0], X[:, 1], c=y, cmap=plt.cm.Spectral)123456789101112131415123456789101112131415

# Plot the decision boundary

plot_decision_boundary(lambda x: clf.predict(x))

plt.title("Logistic Regression")123123

The graph shows the decision boundary learned by our Logistic Regression classifier. It separates the data as good as it can using a straight line, but it’s unable to capture the “moon shape” of our data.

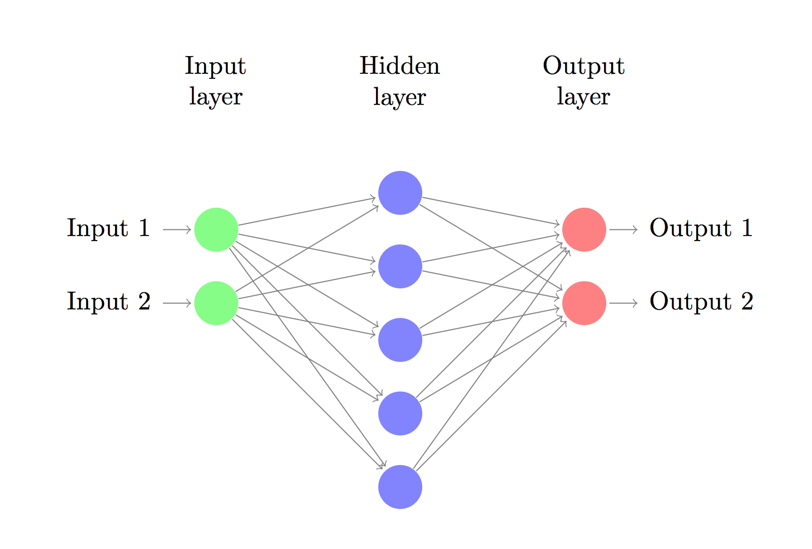

训练一个神经网络

现在,我们搭建由一个输入层,一个隐藏层,一个输出层组成的三层神经网络。输入层中的节点数由数据的维度来决定,也就是2个。相应的,输出层的节点数则是由类的数量来决定,也是2个。(因为我们只有一个预测0和1的输出节点,所以我们只有两类输出,实际中,两个输出节点将更易于在后期进行扩展从而获得更多类别的输出)。以x,y坐标作为输入,输出的则是两种概率,一种是0(代表女),另一种是1(代表男)。结果如下:

神经网络作出预测原理

神经网络通过前向传播做出预测。前向传播仅仅是做了一堆矩阵乘法并使用了我们之前定义的激活函数。如果该网络的输入x是二维的,那么我们可以通过以下方法来计算其预测值 :

z1a1z2a2=xW1+b1=tanh(z1)=a1W2+b2=y^=softmax(z2)

zi is the input of layer i and ai is the output of layer i after applying the activation function. W1,b1,W2,b2 are parameters of our network, which we need to learn from our training data. You can think of them as matrices transforming data between layers of the network. Looking at the matrix multiplications above we can figure out the dimensionality of these matrices. If we use 500 nodes for our hidden layer then W1∈R2×500, b1∈R500, W2∈R500×2, b2∈R2. Now you see why we have more parameters if we increase the size of the hidden layer.

研究参数

Learning the parameters for our network means finding parameters (W1,b1,W2,b2) that minimize the error on our training data. But how do we define the error? We call the function that measures our error the loss function. A common choice with the softmax output is the cross-entropy loss. If we have N training examples and C classes then the loss for our prediction y^ with respect to the true labels y is given by:

L(y,y^)=1N∑n∈N∑i∈Cyn,ilogy^n,i

The formula looks complicated, but all it really does is sum over our training examples and add to the loss if we predicted the incorrect class. So, the further away y (the correct labels) and y^ (our predictions) are, the greater our loss will be.

Remember that our goal is to find the parameters that minimize our loss function. We can use gradient descent to find its minimum. I will implement the most vanilla version of gradient descent, also called batch gradient descent with a fixed learning rate. Variations such as SGD (stochastic gradient descent) or minibatch gradient descent typically perform better in practice. So if you are serious you’ll want to use one of these, and ideally you would also decay the learning rate over time.

As an input, gradient descent needs the gradients (vector of derivatives) of the loss function with respect to our parameters: LW1, Lb1, LW2, Lb2. To calculate these gradients we use the famous backpropagation algorithm, which is a way to efficiently calculate the gradients starting from the output. I won’t Go into detail how backpropagation works, but there are many excellent explanations (here or here) floating around the web.

Applying the backpropagation formula we find the following (trust me on this):

δ3=yy^δ2=(1tanh2z1)°δ3WT2LW2=aT1δ3Lb2=δ3LW1=xTδ2Lb1=δ2

实现

Now we are ready for our implementation. We start by defining some useful variables and parameters for gradient descent:

num_examples = len(X) # training set size nn_input_dim = 2 # input layer dimensionality nn_output_dim = 2 # output layer dimensionality # Gradient descent parameters (I picked these by hand) epsilon = 0.01 # learning rate for gradient descent reg_lambda = 0.01 # regularization strength12345671234567

First let’s implement the loss function we defined above. We use this to evaluate how well our model is doing:

# Helper function to evaluate the total loss on the dataset def calculate_loss(model): W1, b1, W2, b2 = model['W1'], model['b1'], model['W2'], model['b2'] # Forward propagation to calculate our predictions z1 = X.dot(W1) + b1 a1 = np.tanh(z1) z2 = a1.dot(W2) + b2 exp_scores = np.exp(z2) probs = exp_scores / np.sum(exp_scores, axis=1, keepdims=True) # Calculating the loss corect_logprobs = -np.log(probs[range(num_examples), y]) data_loss = np.sum(corect_logprobs) # Add regulatization term to loss (optional) data_loss += reg_lambda/2 * (np.sum(np.square(W1)) + np.sum(np.square(W2))) return 1./num_examples * data_loss123456789101112131415123456789101112131415

We also implement a helper function to calculate the output of the network. It does forward propagation as defined above and returns the class with the highest probability.

# Helper function to predict an output (0 or 1) def predict(model, x): W1, b1, W2, b2 = model['W1'], model['b1'], model['W2'], model['b2'] # Forward propagation z1 = x.dot(W1) + b1 a1 = np.tanh(z1) z2 = a1.dot(W2) + b2 exp_scores = np.exp(z2) probs = exp_scores / np.sum(exp_scores, axis=1, keepdims=True) return np.argmax(probs, axis=1)1234567891012345678910

Finally, here comes the function to train our Neural Network. It implements batch gradient descent using the backpropagation derivates we found above.

# This function learns parameters for the neural network and returns the model.

# - nn_hdim: Number of nodes in the hidden layer

# - num_passes: Number of passes through the training data for gradient descent

# - print_loss: If True, print the loss every 1000 iterations

def build_model(nn_hdim, num_passes=20000, print_loss=False):

# Initialize the parameters to random values. We need to learn these.

np.random.seed(0)

W1 = np.random.randn(nn_input_dim, nn_hdim) / np.sqrt(nn_input_dim)

b1 = np.zeros((1, nn_hdim))

W2 = np.random.randn(nn_hdim, nn_output_dim) / np.sqrt(nn_hdim)

b2 = np.zeros((1, nn_output_dim))

# This is what we return at the end

model = {}

# Gradient descent. For each batch...

for i in range(0, num_passes):

# Forward propagation

z1 = X.dot(W1) + b1

a1 = np.tanh(z1)

z2 = a1.dot(W2) + b2

exp_scores = np.exp(z2)

probs = exp_scores / np.sum(exp_scores, axis=1, keepdims=True)

# Backpropagation

delta3 = probs

delta3[range(num_examples), y] -= 1

dW2 = (a1.T).dot(delta3)

db2 = np.sum(delta3, axis=0, keepdims=True)

delta2 = delta3.dot(W2.T) * (1 - np.power(a1, 2))

dW1 = np.dot(X.T, delta2)

db1 = np.sum(delta2, axis=0)

# Add regularization terms (b1 and b2 don't have regularization terms)

dW2 += reg_lambda * W2

dW1 += reg_lambda * W1

# Gradient descent parameter update

W1 += -epsilon * dW1

b1 += -epsilon * db1

W2 += -epsilon * dW2

b2 += -epsilon * db2

# Assign new parameters to the model

model = { 'W1': W1, 'b1': b1, 'W2': W2, 'b2': b2}

# Optionally print the loss.

# This is expensive because it uses the whole dataset, so we don't want to do it too often.

if print_loss and i % 1000 == 0:

print ("Loss after iteration %i: %f" %(i, calculate_loss(model)))

return model1234567891011121314151617181920212223242526272829303132333435363738394041424344454647484950515253545512345678910111213141516171819202122232425262728293031323334353637383940414243444546474849505152535455一个隐藏层规模为3的网络

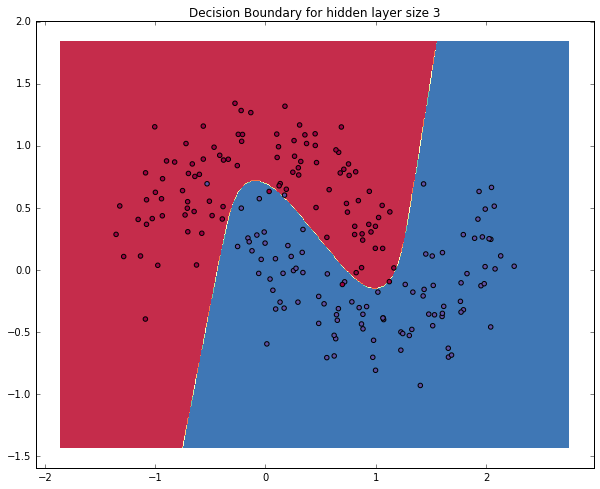

Let’s see what happens if we train a network with a hidden layer size of 3.

# Build a model with a 3-dimensional hidden layer

model = build_model(3, print_loss=True)

# Plot the decision boundary

plot_decision_boundary(lambda x: predict(model, x))

plt.title("Decision Boundary for hidden layer size 3")123456123456Loss after iteration 0: 0.432387 Loss after iteration 1000: 0.068947 Loss after iteration 2000: 0.069541 Loss after iteration 3000: 0.071218 Loss after iteration 4000: 0.071253 Loss after iteration 5000: 0.071278 Loss after iteration 6000: 0.071293 Loss after iteration 7000: 0.071303 Loss after iteration 8000: 0.071308 Loss after iteration 9000: 0.071312 Loss after iteration 10000: 0.071314 Loss after iteration 11000: 0.071315 Loss after iteration 12000: 0.071315 Loss after iteration 13000: 0.071316 Loss after iteration 14000: 0.071316 Loss after iteration 15000: 0.071316 Loss after iteration 16000: 0.071316 Loss after iteration 17000: 0.071316 Loss after iteration 18000: 0.071316 Loss after iteration 19000: 0.071316 <matplotlib.text.Text at 0x1e88c060898>

Yay! This looks pretty good. Our neural networks was able to find a decision boundary that successfully separates the classes.

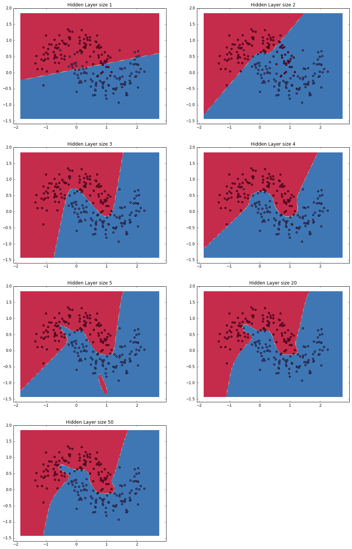

变更隐藏层规模

In the example above we picked a hidden layer size of 3. Let’s now get a sense of how varying the hidden layer size affects the result.

plt.figure(figsize=(16, 32))

hidden_layer_dimensions = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 20, 50]

for i, nn_hdim in enumerate(hidden_layer_dimensions):

plt.subplot(5, 2, i+1)

plt.title('Hidden Layer size %d' % nn_hdim)

model = build_model(nn_hdim)

plot_decision_boundary(lambda x: predict(model, x))

plt.show()1234567812345678

We can see that while a hidden layer of low dimensionality nicely capture the general trend of our data, but higher dimensionalities are prone to overfitting. They are “memorizing” the data as opposed to fitting the general shape. If we were to evaluate our model on a separate test set (and you should!) the model with a smaller hidden layer size would likely perform better because it generalizes better. We could counteract overfitting with stronger regularization, but picking the a correct size for hidden layer is a much more “economical” solution.

11

上一篇: python3网络编程之socket

下一篇: Centos7安装Python3的方法

- openvpn linux客户端使用

52253

- H3C基本命令大全

52168

- openvpn windows客户端使用

42312

- H3C IRF原理及 配置

39192

- Python exit()函数

33685

- openvpn mac客户端使用

30639

- python全系列官方中文文档

29349

- python 获取网卡实时流量

24307

- 1.常用turtle功能函数

24190

- python 获取Linux和Windows硬件信息

22555

- LangChain 1.0-Agent中间件-实现闭环(批准-编辑-拒绝动作)

156°

- LangChain 1.0-Agent中间件-汇总消息

153°

- LangChain 1.0-Agent中间件-删除消息

162°

- LangChain 1.0-Agent中间件-消息压缩

154°

- LangChain 1.0-Agent中间件-多模型动态选择

204°

- LangChain1.0-Agent-部署/上线(开发人员必备)

373°

- LangChain1.0-Agent-Spider实战(爬虫函数替代API接口)

408°

- LangChain1.0-Agent(进阶)本地模型+Playwright实现网页自动化操作

406°

- LangChain1.0-Agent记忆管理

385°

- LangChain1.0-Agent接入自定义工具与React循环

423°

- 姓名:Run

- 职业:谜

- 邮箱:383697894@qq.com

- 定位:上海 · 松江